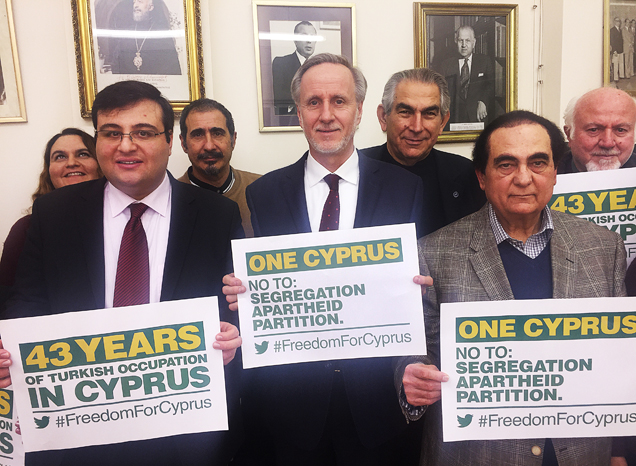

Lobby for Cyprus recently welcomed Vahan Krikorian of the Armenian National Committee of the United Kingdom (ANC UK) to its monthly General Council Meeting, where Vahan gave a presentation, ‘Nagorno-Karabakh: the Armenians’ Cyprus’. We look forward to a working with ANC UK and cooperating with our friends in the Armenian community on various projects and events in the near future.

Nagorno-Karabakh: the Armenians’ Cyprus

Mr Theodorou, Co-ordinator for Lobby for Cyprus, ladies and gentlemen, it gives me great pleasure to join you at this meeting of Lobby for Cyprus, and I am deeply honoured to able to speak to you today. The Armenian people have always been fraternally close to the Greek people, both in Cyprus and Greece, and we both have shared, and continue to share, the pain of Turkish aggression – an aggression that shows no sign of abating, as seen with the continued hostility and behaviour perpetrated by Turkey against Cyprus, Greece and Armenia. This evening, I wish to talk about another sphere of Turkic hostility: that of the aggression of Azerbaijan, a close ally of Turkey, against the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Mr Theodorou, Co-ordinator for Lobby for Cyprus, ladies and gentlemen, it gives me great pleasure to join you at this meeting of Lobby for Cyprus, and I am deeply honoured to able to speak to you today. The Armenian people have always been fraternally close to the Greek people, both in Cyprus and Greece, and we both have shared, and continue to share, the pain of Turkish aggression – an aggression that shows no sign of abating, as seen with the continued hostility and behaviour perpetrated by Turkey against Cyprus, Greece and Armenia. This evening, I wish to talk about another sphere of Turkic hostility: that of the aggression of Azerbaijan, a close ally of Turkey, against the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh.

History

Perhaps before I outline this conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, it might be prudent for me to give a brief history of this area. Nagorno-Karabakh has formed part of Armenia throughout its history – it was part of the historic Armenian province of Artsakh, and its Armenian roots reach back to before the first millennium BC. Testament to its Armenian ancestry are, of course, the various churches and monasteries that were built by the Armenians, such as the Gandazar monastery built in the 10th century. As Armenia itself became partitioned and subsumed into various competing empires, Armenian princely dynasties presided over Karabakh, guaranteeing its sovereignty through treaty arrangements with different powers. This power play continued over the centuries, and by the nineteenth century, following the Russo-Persian war, the Russian empire annexed Karabakh in 1805. The name Nagorno-Karabakh itself is not Armenian but rather a combination of Russian, Turkish and Persian that literally translates as “Black Mountainous Garden” and this perhaps vividly demonstrates the influence of external powers on its history.

Following the Russian revolution and collapse of the Russian Empire, the independent republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan emerged, the latter a Turkic nation that was strongly allied to the Ottoman Empire. As a result, Azerbaijan, aided by the Ottoman Empire and then Turkey, entered into a dispute with Armenia over Karabakh that resulted in twenty per cent of the Armenian population being killed. With this situation coming to the attention of world powers, the League of Nations acknowledged Nagorno-Karabakh’s disputed status and refused to admit Azerbaijan as a member state because of its dispute with Armenia.

Sovietisation

The violence continued but came to a standstill in 1920, when the whole Caucasus region became part of the recently founded Soviet Union. In 1921, however, Stalin, as Commissar of Nationalities in the Soviet Union, determined that Karabakh should be included within the boundaries of Soviet Azerbaijan; indeed, this Stalinist practice of manipulating borders in the Caucasus would continue to influence later Soviet policy. Why did Stalin undertake this action? Quite simply, he believed that by mixing Armenian Christians with Muslim Azeris, this would foster national harmony. The Soviet Union also had plans to develop Turkey as a communist state, and this step would also naturally please them. To legitimise this false annexation, the communists decided that Karabakh would have autonomous status within Azerbaijan; this ensured that the physical and geographical ties with Armenia were destroyed whilst also maintaining a false “pretence” of autonomy for the now Armenian minority. As a result, throughout the entire Soviet period, the civil, political, socio-economic and cultural rights of the Armenian population were discriminated against by the Azeri government.

Dissolution of the Soviet Union

Despite living under a totalitarian system, however, the Armenian population continued to advocate for the liberation of their area from Azeri control; indeed, with the perestroika and glasnost reforms (initiated by Gorbachev), Armenians were further encouraged to break free of Azeri control and, in February 1988, a formal request was made to the highest legislative bodies in the Soviet Union to transfer Karabakh to Armenia. Unfortunately, the Azeri government retaliated by carrying out brutal massacres against the Armenian population such as the pogrom committed in Sumgait, the third largest city in Azerbaijan, in February 1988.

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union now looming, in 1991 Nagorno-Karabakh initiated the legal process, under Soviet law, to declare independence from Azerbaijan. On 10th December 1991, in full compliance with Soviet law, Karabakh held a referendum on independence in the presence of international observers; the population overwhelmingly voted in favour of independence and the newly independent Nagorno-Karabakh republic created legitimate governmental institutions. On January 6th, 1992, the newly convened parliament adopted the Declaration of Independence on the basis of the referendum results.

Karabakh War

The reaction by Azerbaijan was all out war against this newly independent republic; this took the form of indiscriminate bombardment and shelling of the Armenian population and ground attacks. By the summer of 1992, Azerbaijan had seized and occupied half the territory of Karabakh, and had displaced the Armenian inhabitants. The Armenians, in response, organised an army and were able, through military operations, to seize back these Azeri held areas and also, crucially, to establish a ground connection to Armenia. This brutal war did, however, come to international attention, with Baroness Caroline Cox, a former deputy speaker of the House of Lords, visiting Karabakh during the war and publicising the atrocities committed by the Azeri forces. Finally, in 1994, following strong counter-offensives by the Armenians, Azerbaijan was forced to accept a Russian-brokered armistice that was signed in May of that year. It should be noted that this ceasefire was signed not only by Armenia and Azerbaijan, but also by Nagorno-Karabakh – recognition in itself for Nagorno-Karabakh as a distinctive political and territorial entity.

Peace Process

Since 1994, there have been attempts to resolve this situation peacefully through the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe, and its so called Minsk process (named after the inaugural peace process that was to take place in the city of Minsk; the conference did not subsequently go ahead because Armenia and Azerbaijan could not agree on whether delegates from Karabakh could themselves attend and be a party to the talks.) However, no agreement was achieved, and since then, Armenia and Azerbaijan have remained at war; until April 2016, only the 1994 armistice prevented a return to the full scale conflict that had begun in the early 1990s.

Aftermath

With no peaceful agreement, the Nagorno-Karabakh situation has been very succinctly described as a “frozen conflict.” Despite this, and despite the fact that it’s unrecognised as a nation state internationally, since the war Nagorno-Karabakh has progressed as a country built upon the twin foundations of democracy and respect for the rule of law: Article I of its Constitution states that “The Karabakh republic is a sovereign, democratic state based on social justice and the rule of law.” It has developed governmental institutions, political parties and held free local, parliamentary and presidential elections. Furthermore, there has been growth in its economy, continued investment in its transport infrastructure and the the development of its mining and energy industries, as well as the important entrenchment of political and civil liberties. This has all been achieved against the backdrop of continued aggression by Azerbaijan and its numerous, irresponsible and sustained efforts to destabilise Nagorno-Karabakh and the entire Southern Caucasus region generally. Indeed, these efforts are clearly demonstrated by the blockade that Azerbaijan, acting in concert with Turkey, has continued to implement against Karabakh that have been condemned internationally (as seen with the US Congress which passed legislation in 1992 restricting direct assistance to Azerbaijan on account of these blockades.)

Azerbaijan, in stark contrast to Nagorno-Karabakh, is a country that is deeply mired in corruption, where human rights and a free press are non-existent and where a kleptocratic political elite continues to enrich itself at the expense of the country’s impoverished population. With an economy solely based on diminishing oil and gas revenues, the government continues its aggression against Nagorno-Karabakh, Armenia and Armenians in general as a way of deflecting the Azeri population from their own economic woes. This deliberate policy of aggression manifested itself in April 2016 when Azerbaijan commenced a new military offensive against Nagorno-Karabakh; through the efforts of the Karabakh army, this action not only failed but was swiftly defeated, with conflict lasting for only four days. Yet it was once again a reminder that, despite losing the war in the 1990s, Azerbaijan still believes that it can settle this conflict purely through outright and aggressive military force.

Position of ANC UK

The position of my organisation, which reflects the view of the diaspora, is that the people of Nagorno-Karabakh, just like the Greek-Cypriot people of Cyprus, have the right to determine their own destiny and not be forced into any other arrangement through hostile acts by enemy countries. In short, we believe that Nagorno-Karabakh has the right to declare itself as an independent nation state. This right to self determination has been reaffirmed through resolutions in the European Parliament, as well as through legal opinions as expressed by the International Court of Justice. Furthermore, Nagorno-Karabakh encompasses all the attributes necessary to be recognised as an independent state as determined by the Montevideo Convention on Rights and Duties of States.

ANC UK continues to advocate for this right to self determination; in the UK, over the past 10 years, we have sought to increase the profile of Nagorno-Karabakh by organising visits by MPs; for example, we took Stephen Pound, MP for Ealing North and Shadow Minister for Northern Ireland, to Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh. We have also facilitated visits to the UK by the former foreign minister of Karabakh, as well as arranging meetings between Karabakh politicians and the Foreign and Commonwealth office. This is part of a worldwide initiative; just recently, our sister organisations within the USA and European Union organised for American Congressman and European MEPs to visit the country, where they noted its very obvious democratic nature and the progress it was making. There has also been progress on Nagorno-Karabakh’s international recognition as a nation state: in Australia, the state of New South Wales has recognised Karabakh; in America, no less than eight states – California, Georgia, Hawaii, Louisiana, Maine, Michigan, Massachusetts and Rhode Island – have recognised Karabakh as an independent country.

Conclusion

I began my speech this evening by noting the close fraternal relationship between the Greek and Armenian people and I would like to end by drawing another parallel: both are an example to the world of the superiority of strength, determination and resilience.

In conclusion, we salute Greece, Armenia, Cyprus and Nagorno-Karabakh as they continue their unwavering stand against Turkish hostility and aggression.

Thank you.